The protest movement also gave birth to a series of icons.

Some became recognisable symbols of the revolution by chance, others by choice.

“Because you are the president’s favourite, everyone is afraid of you and prays to you.”

Margarita Levchuk was six years old when Lukashenko became president.

Twenty years later, and with Lukashenko claiming his fifth consecutive term in office, Levchuk met him in person in December 2019. She was already one of the most famous Belarusian opera singers, her soprano voice having echoed at the Bolshoi Theatre in Minsk and in packed halls across Europe.

Then she attended the opening of a luxury restaurant. No one had known that Lukashenko would also be there. The restaurant was built in one of the central parks in Minsk. Construction there is normally forbidden – unless you have a blessing from the regime.

Margarita and Lukashenko were brought together by alcohol – he shoved a glass of cognac into her hand.

“He says to me, ‘what are you drinking?’ I say, ‘champagne’. He says: ‘Give it here, I will pour you a drink you will never taste again in your life.’”

Lukashenko then poured her a glass of 140-year-old cognac.

Facing him for the first time, she turned to a topic she knew best – opera. Now, she thought, she had a unique chance to invite Lukashenko to a play.

“Lukashenko only loves ice hockey. [...] He spent 27 years in power and he has never been to an opera theatre.”

Her plan worked – he agreed to come. “I don’t like opera? I love opera,” Lukashenko exclaimed.

At the time, Margarita had already considered leaving the Bolshoi theatre, because she did not want to be seen as a supporter of the regime.

She knew that Lukashenko would probably never make it to the opera. Regardless, after she announced to her colleagues that the man himself would be in attendance, everyone rushed to put on the best show they could. She watched the absurdly grandiose preparations unfold in front of her.

“I laughed at them, I mocked them. They all ran, panicking, back and forth. Of course, I understand it’s bad to behave this way. [...] But to use people like this only because they worship Lukashenko – this was really funny.”

“There, everyone is so afraid of him,” she adds.

Once you are seen as being close to the regime, “you can open doors with your feet”.

The result was a grand display of Verdi's Traviata in February 2020.

It was also the last time Margarita performed at the Bolshoi Theatre.

Choosing the side of the opposition meant letting go of everything she had built up in her career.

Many artists, as well as professional athletes, depend on financial support doled out by the state. But then, the titles they win are no longer considered theirs, but rather the pride of the regime.

“You are simply a slave and that’s it.”

The first step for Margarita to break away from the regime was a post on Instagram.

She wrote “Zhyve Belarus” – the ‘Long Live Belarus’ slogan associated with the opposition.

“You understand that for the words ‘Zhyve Belarus’ you get a prison sentence, immediately.”

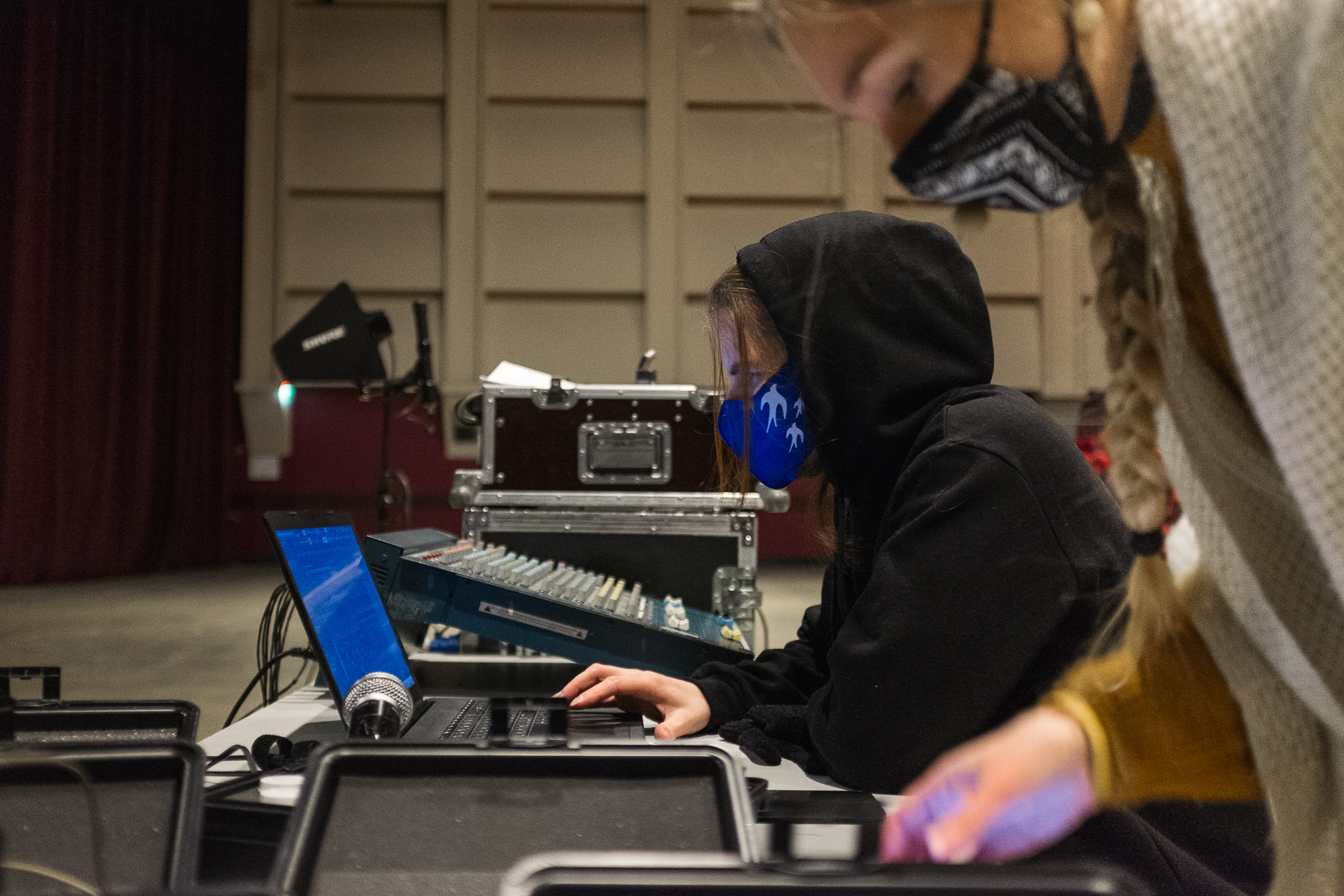

Margarita and her partner, Andrey Pauk, perform during an event at the Belarusian university in exile, the European Humanities University (EHU). The liberal arts university was closed down by the regime in 2004, forcing it to move to Vilnius.

In October, Margarita joined the National Crisis Committee as a presumptive minister of culture.

When she departed for Vilnius to appear at a concert, she was warned not to return to Minsk. She had allegedly been blacklisted.

“And then I thought to myself, ‘thank you opera’. It saved me.”

Margarita inside her studio at the Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre (LNOBT).

Over the course of a few months, she went from a regime darling to an enemy. Even though in Vilnius she could continue to do what she loved – sing – she paid a price for choosing the side of the opposition.

“I can't go back to Belarus, [even though] I want to live in my homeland,” says Margarita. “And I knew, of course, that it would be so.”

Thoughts about her personal safety have also intensified after Lukashenko diverted a Vilnius-bound Ryanair flight to Minsk in May 2020 to detain Roman Protasevich, a key activist and dissident journalist working from Lithuania.

After the incident, which brought renewed protests and international condemnation, leading opposition figures reshuffled their security protocols in Lithuania. It was done after news broke that there had been an apparent infiltration by the Belarusian secret services.

“I have moved to a different location and I was warned – never disclose your address, every person, even your friend, could be working for Lukashenko,” says Margarita.

Her family has already been visited by the Belarusian KGB.

Margarita walks inside the theatre in Vilnius. She is trying to get in touch with her family in Belarus, who were recently approached by the KGB. “We agreed to call, I hope they are okay,” she says.

Months after she fled Belarus, she was inundated with unusual invitations to perform in Moscow. Here, according to Belarusian and Russian producers that contacted her, she would have a breathtaking career.

All she had to do was come to Moscow.

Margarita had never received invitations like this before. To her, it looked like a KGB set-up.

“In Moscow, they can simply shove you into a car boot and take you to Belarus. And then I would end up together with Roman Protasevich.”

After she refused the overtures, the regime announced a criminal case against her. The main charge – alleged desecration of the Belarusian flag in one of the videos filmed in Vilnius together with a known Belarusian blogger, Andrey Pauk.

Margarita and Andrey inside their studio in Vilnius. They asked not to reveal its location.

Their duet – Красная Зелень (Red Greens) – picks at the absurdity of the Belarusian regime.

One of their more popular episodes features a remake of a Soviet-era nursery rhyme, mocking the criminal case against Margarita. It racked up more than half a million views on YouTube.

Their satire has become a political weapon, says Margarita. It is now wielded by the same girl who, a year ago, was poured cognac by Lukashenko.

According to Margarita, this is a huge insult to Lukashenko.

“He remembers everyone and, of course, he is very angry, because I sang for him. He adored me, and now I mock him.”

Margarita and her partner have become darlings among the reloants. However, they do not see themselves as their icons, stressing that there are no boundaries between those who had stayed, and those who were forced to leave.

When asked what she would tell Lukashenko if she saw him today, Margarita mentions Raman Bandarenka, a former soldier-turned-protester. He was grabbed by security forces during a vigil at a protest site, turning up dead several hours later. The regime tried to cover up the apparent murder.

“Who killed Roma? Roma was killed in Peremen Square [and] until today there has been no investigation.”

“Then I would ask a bunch of other questions, how many deaths we still don’t know about.”

Peremen Square 2.0 in Vilnius, a copy of the one in Belarus where Bandarenka was detained. The iconic image features two Belarusians DJs who played the protest anthem Peremen (Changes) at a pre-election rally in Minsk, leading to their persecution and a subsequent exile to Lithuania.

Vlad was one of them. “I was pulled into nonsense that I had never agreed to.”

On August 6, 2020, just three days before the presidential election, Vladislav (Vlad) Sokolovski, a sound engineer working for a state firm, became an unlikely symbol of the Belarusian opposition.

Although the regime banned opposition rallies, aiming to physically deter them by filling popular squares and parks with impromptu state events, hundreds of supporters of Lukashenko’s opponents swarmed the scene.

In front of the largely silent crowd, Vlad stood at the sound table with his colleague, Kirill Galanov.

They seized the moment.

Blasting through the air, the sound of Peremen (Changes) by Viktor Tsoy, which had already become the rallying cry, ignited the thousands of white-clad protesters.

The largely silent crowd, that had anxiously looked upon the swarms of police to anticipate their actions, burst into anti-Lukashenko chants.

The captured images of them towering above the sound mixer on August 6, however, took upon a life of their own.

Numerous posters and murals turned them into symbols recognisable to the majority of Belarusians. Their silhouettes also became the centre-piece of the Peremen Square.

“As soon as [the murder of Raman Banadarenka] happened, I started getting messages and calls,” says Vlad in Vilnius. “‘There needs to be a reaction, because a person was killed in your square.’ First of all, why is it mine?”

“I said from the beginning that this mural was not created by me. The meaning that the mural acquired was created by the [Belarusian] people.”

The image of Vlad and Kirill as two brothers-in-arms was also created by the media. “We are colleagues, we have a normal relationship, but it was never like we were very good friends.” They simply did what they could at the time, he adds

As Lithuania had been plunged into another, tighter winter quarantine in late 2020, Vlad was walking around town, joining streams of other people seeking a break from the lockdown boredom.

Speaking in his animated voice, he recalled persistent attempts to resurrect him as an icon.

“Around New Year’s eve, things started happening to do with the August 6 events. [...] I received various stupid offers: ‘Let’s do it again, like you press the button.’”

“Then, ‘let’s film a music video about the killing of Raman Bandarenka’.”

“I was pulled into nonsense that I had never agreed to. [...] I did what I did not because, for the rest of my life, I will play the role of the guy who pressed the button.”

At some point, the requests became more dramatic. “‘I am turning to you like a hero, but you cannot help us.’”

Throughout the year, he largely stayed away from Belarusian protests organised in Vilnius.

“For many people it’s a source of pride: ‘I sat [in prison], I am a revolutionary.’ The whole essence [...] is to create an image,” he says. “I am not saying everyone is like this, but there are types [of people] like that.”

Vlad in Vilnius, weeks after his arrival in Lithuania, September 2020. He is standing in front of Vilnius Sports and Culture Palace, a dilapidated Soviet-era wreck. Over 30 years ago, it hosted the first meeting of Lithuania’s independence movement, Sąjūdis.

According to Vlad, many relocants in Vilnius remain stuck in the August days.

“It’s 100-percent true that most Belarusians here are still living in that time.”

“Speaking about what I did, I have said from the very beginning: there is nothing special in it. I don’t like how it became seen, that’s why I have distanced myself from everything.”

He now lives together with his girlfriend, who has asked to remain anonymous as she has never appeared in protests, or in Vlad’s subsequent media spotlight. She still has a luxury that Vlad doesn’t – she can return to Minsk.

In Lithuania, they initially received help by members of the diaspora, who assisted Vlad in finding a place to live and work.

He got a job as a sound engineer for a production about Viktor Tsoy, the very same artist whose song Changes became one of the Belarusian protest anthems.

In 2021, Vlad says he is building a future that he wants.

Not all Belarusians are in the same position, Vlad adds.

“This is the mentality of Belarusians. You come with your ‘small Belarus’ and you continue living there [...] because it is comfortable.”

Meeting at the Compensa concert hall in Vilnius, he shows off his rearrangement of Kino’s most popular tracks.

“See if you like this one,” he says, putting on a remake of the famous song Kukushka, blaring the unmistakable chords across the hall.

“I really think that a person needs to think about himself first. Because how else can you think of something, when you cannot fix your life?”

“We came here, but we sit as if waiting for something, like something will happen by itself. What happens here [in Lithuania] is very different from what goes on there [in Belarus].”

Here, there is not much activism besides “waving flags”, he adds.

“Some time has passed, everyone has hidden themselves [in Belarus], wanting to work again for their cents [...] That’s why I don’t have such optimism.”

On the first anniversary of the August 9 protests, Vlad agreed to appear on stage with the many other Belarusians that had become symbols of the revolution.

He could not refuse a request from someone in the diaspora who had helped him personally, according to Vlad.

The only point of these protests for the Belarusians in Lithuania is “psychotherapeutic”, to give meaning to why they were forced to flee and a way to continue their activism, says Vlad.

“If you look at all of this sceptically, maybe you will notice something. You do not expect that anyone will do anything for you.”

“When my sister picked up the phone she swore, cried, and hung up.”

Yauhen Zaichkin laid on the ground, unconscious, with his eyes wide open. Above, an OMON riot police officer waved his hands erratically, calling for an ambulance to come over.

On August 9, 2020, Yauhen would be falsely pronounced the first victim of the regime crackdown against protesters.

The actual first fatality would come a day later, on August 10.

The officer in a balaclava, meanwhile, would become the centrepiece in regime propaganda, appearing in interviews and claiming he was attempting to save Youhen’s life – even while scores of detained protesters were being beaten and later tortured in Minsk prisons.

On that first night of the post-election protests, Zaichkin spent hours in hospital. Once he was conscious, a doctor urged him to leave before the police arrived.

With his phone broken, he wasn’t able to respond to frantic calls from friends and family.

Finally, his sister managed to get through to him. “[She] heard my voice, swore, and hung up.”

After the ordeal, Yauhen became one of the first relocants to arrive in Lithuania in late August 2020.

Yauhen at temporary accommodation together with several other Belarusians, August 2020. He crossed the border into Lithuania just days prior.

“After crossing the border, I thought it would be over before the end of August. Then I thought it would last until the end of autumn,” remembers Yauhen a year later. “Then everyone expected it to be over before the New Year. But right now everyone understands that it will take more time.”

Once in Lithuania, he joined the protests here immediately. His picture was among the images displayed in front of the Belarusian embassy in Vilnius.

The early protests in front of the Belarusian embassy in August 2020 would draw the local diaspora, as well as the recent arrivals. The numbers eventually started to dwindle.

The Belarusian diplomats had initially agreed to a dialogue, according to members of the diaspora community and local activists. However, as the regime grip tightened in Minsk, so did the embassy’s position.

His photo has become a recognisable symbol for most Belarusians.

Even today, people regularly ask him the same question – are you ‘that’ guy?

“These guys who arrive [in Lithuania], some of them recognise me [...]. Everyone says the same thing – they were really worried at the time, but were happy that it all ended well. But they all remember the photos.”

When asked if he considers himself a symbol, Yauhen pauses. “Well, I guess, I’m a symbol.” But only “of the protests in the early days,” he adds.

Being recognised by other relocants, however, is not a burden. It merely helps establish that he is one of them.

“I remember that when I came here, I didn’t talk to everyone. Because I didn’t know what kind of person I was talking to.”

Belarusians have always been careful about being followed by the KGB – even in Lithuania. The Ryanair plane incident, as well as the murder of a Belarusian activist in Ukraine, only amplified their worries.

Yauhen at the protest camp in Medininkai. Read more in Part One.

Now, the others can be sure that “I can’t be on the side [of the regime] because I was at these protests, I was beaten, and I am here for that reason”.

This helps his work with the recent arrivals, who need help once they flee to Lithuania.

“I take part in helping all the new arrivals,” he says. “When they cross the border, they make one post [online], and by the evening [other relocants] hand them a few bags with food, some other stuff.”

Yauhen lives in one of Vilnius’ suburbs. It’s yet another small community of Belarusians living under the same roof. Around them, the Soviet-era housing blocks seem not much different from the ones in Minsk.

As for other relocants, it hasn’t been easy for him to obtain a legal status in the country.

Although Yauhen has been able to find work – mostly because painters and decorators are in high demand – he has found himself entangled in Lithuanian bureaucracy. Due to the stalling asylum process, he has withdrawn his claim, opting for a work visa instead.

In Vilnius, “I feel like I just moved to another city from Minsk,” says Yauhen. Even the climate here is “exactly the same”.

While Yauhen builds his life here, his son has remained in Belarus. Because the boy is underage and the regime has placed additional barriers to leave the country, Yauhen hasn’t seen his son since arriving in Lithuania.

For now, all he can do is send some money over the border.

In March, Yauhen was seen walking along a giant Belarusian flag, strewn out across central Vilnius in a protest to mark the alternative Belarusian independence day celebrated by the opposition.

The air was filled with chants “Ačiū Lietuva” – thank you, Lithuania.

Then, Lithuania was once again considering to close the borders to stem the spread of the coronavirus. Hearing the news, Yauhen was worried he would no longer be able to look for work outside the country.

“Damn. I should probably start looking for an apartment,” he said.

Half a year later, in summer 2021, he is eyeing a step further.

“I applied for asylum and have come to terms with the fact that I will have to become a Lithuanian resident[?] for the next five years”.

Later, he says he plans to apply for the Lithuanian citizenship.

“If nothing changes there [in Belarus], I will slowly start to get into this Lithuanian life.”

Soon, he says, he will become just like any other Lithuanian citizen – only without the right to vote.

The new documents will also guarantee the right to travel.

“But the only country in the world where I won’t be able to go is Belarus.”